On Sunday, March 14th, we’ll spring forward one hour. We think of it as losing one hour of sleep–but what’s actually happening is that you are asking your body to behave more like a morning person for the next 8 months of the year. Here’s why that’s pretty simple for kids, difficult for some adults, and downright awful for teenagers.

For little ones, springing forward an hour is usually a pretty painless ordeal.

Unless you have to wake your child at a certain time in order to get them to daycare or preschool, the time change means that they appear to sleep in an hour later in the morning.

If having your child get up later in the morning isn’t a problem for you, there’s very little that you need to do for this time change. You’ll start putting your child to bed an hour earlier than you were doing on standard time, and everything will shift into place again after a few days.

You can make the adjustment gradually by moving meals and bedtime earlier by 15-20 minutes each day prior to the transition to make for a smoother process. Easy peasy.

It’s not such smooth sailing for adults.

Adults are more likely to feel the effects of trying to get up an hour earlier. Your chronotype is your natural preference for when you go to bed and wake up. One way of measuring this is to calculate the mid-point of your sleep on free days. So if on Saturday night you go to bed at midnight and wake up at 8am, the mid-point of your sleep is 4am. In one survey of American adults, 25% had a mid-point of 4am or later. The later your chronotype, the more likely you are to be at odds with social time, which often demands that work starts earlier than your body would choose to be awake.

The challenge is, we weren’t designed to live on shortened sleep. Unlike food, which naturally moves in seasons of plenty and scarcity, the body does not have a coping mechanism for banking sleep. We can store fat in our cells to be able to survive without food for a short time, but you cannot store sleep. As it turns out, changing the social clock by just one hour makes a difference.

Even aside from the spring time change, Monday mornings are marked by the highest rate of heart attacks. Staying up late over the weekend delays your body’s internal timing and steals away your sleep when the alarm clock goes off on Monday morning, cutting short the stress reduction, reduced heart rate, and decreased blood pressure that sleep offers.

Sadly, this Monday phenomenon is amplified on the Monday following the spring time change. A study looking at the rate of heart attacks in Michigan hospitals between 2010 and 2013 confirmed what previous studies had suggested: there was a 24% increase in patients admitted for heart attacks on the Monday after the clocks move forward. Conversely, they found a 21% decrease in heart attacks after the clocks move back and we gain an extra hour of sleep in the fall.

Heart attacks are at the extreme of what losing an hour of sleep does to our bodies: it’s an example of what the time change does when there are other underlying factors and a history of lost sleep over time. Thankfully, the consequences aren’t as severe for most of us. This simply gives us a sharp awareness of how serious it can be when we don’t live within our biological need for a consistent bedtime and wake time, with sufficient good rest in between.

So why is the time change not as hard on kids?

Most children are early birds. Their natural tendency is to feel sleepy shortly after sunset, and wake with sunrise. Waking up naturally at a consistent time, when your body is ready to wake up, is a big part of getting healthy rest.

The trouble comes if you need to wake your child in the morning. This means either bedtime is too late, or the start to your day is earlier than your child’s internal clock is telling him or her to wake up. Artificially waking your child means that they aren’t getting the tail end of their night of sleep. (The same is true for you if you if an alarm clock–or your child–is waking you in the morning.)

If this is already happening, or you suspect you’ll need to wake your child after the time change, it’s a good idea to start moving bedtime earlier now. For tips on making an early bedtime easier, you can check out my post on 6 Ways to Help Your Child Fall Asleep Faster.

In an ideal world, everyone would go to bed when they naturally feel sleepy, then wake at their body’s natural time. But between work schedules and kids, few adults are able to get the full night of sleep they need. That artificial waking in the morning is what takes away needed sleep, especially for night owls.

Early birds have an easier time switching to daylight saving time.

Their internal clocks are already telling them it’s time to sleep shortly after the sun goes down, and they wake with the first light of morning.

Culturally though, we’ve lost touch with just how in sync our bodies are meant to be with the rise and fall of the sun. Generational comparisons show that as parents we’re putting our children to bed later, even though they still wake with the sun as children always have.

When we move bedtime earlier by an hour for the time change, for many children, this actually helps them repay some of the sleep debt they’ve accumulated from a bedtime that’s been too late.

Night owls struggle with the time change.

Their internal clock needs more time to pass after the sun goes down before they’re ready to sleep, as compared with larks. They still need just as much sleep time as their peers though, so the social clock tends to be rough on night owls. School and work schedules start bright and early, regardless of what individual bodies need.

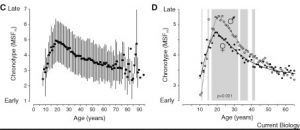

This means that the ones who have the hardest time with the switch to daylight saving time are teenagers. Our body clocks shift significantly later in direct connection with puberty. By age 20, we reach our latest bedtimes, before the internal clock starts working its way earlier again. Because of this, early school start times already cut into the amount of sleep that teens need. Trying to adjust to an even earlier time is painfully difficult for teens, and for adults who are natural night owls.

The graph here shows the rise and fall of this change, with the average marked in black dots in the image on the left. The vertical lines show the difference in chronotype, with night owls at the top, and early birds at the bottom. The chart on the left shows the difference between males and females.

The graph here shows the rise and fall of this change, with the average marked in black dots in the image on the left. The vertical lines show the difference in chronotype, with night owls at the top, and early birds at the bottom. The chart on the left shows the difference between males and females.

While young children can get used to the time change pretty quickly, night owls with a late chronotype can take up to three weeks before they don’t show signs of daytime sleepiness as a result of the change. There’s even some evidence that we never really adjust to daylight saving time at all.

What can you do?

In the time leading up to the beginning of daylight saving time, let lots of light into your child’s room in the morning. Since sunrise is moving earlier, this should bring your child’s wake time earlier with it. If you can, get outside for 15 minutes early in the morning. More time outside throughout the day will also help you and your child fall asleep earlier.

In the evening, shift your meal times along with your bedtime routine, to help your child ease in to the earlier bedtime.

As a parent, this is a good time to make sure you’re following healthy sleep habits for yourself, too. Give yourself some down time before bed, and plug your electronic devices in to charge somewhere outside of the bedroom. A bedtime routine can help you fall asleep easier, just like it does for your child. As much as you’re able, try to go to bed at the same time every night and wake up at the same time every morning. Your mind and body will thank you.